The Theory Trap: Why Your Last Training Was a Waste of Time

We’ve all been there. A calendar invite appears for a "Mandatory Agile Introduction." You walk into a room (or join a Zoom call) and for two to three hours, someone dumps a hundred slides of theory onto you.

Frankly, it’s a waste of time. I see this in my own corporate world. I give a two-hour Agile introduction. Usually, only half the invited people show up. Those who do are often "hiding" behind their laptops. I’m not proud of that specific course, but it has taught me a brutal truth: Information dumping in an information-obese world is a recipe for failure.

Our attention spans are not just shrinking; they are being rewired. Between doom-scrolling and short-form videos, our brains are addicted to instant "traction." When we sit through theory-heavy training, we are fighting a losing battle with our own biology.

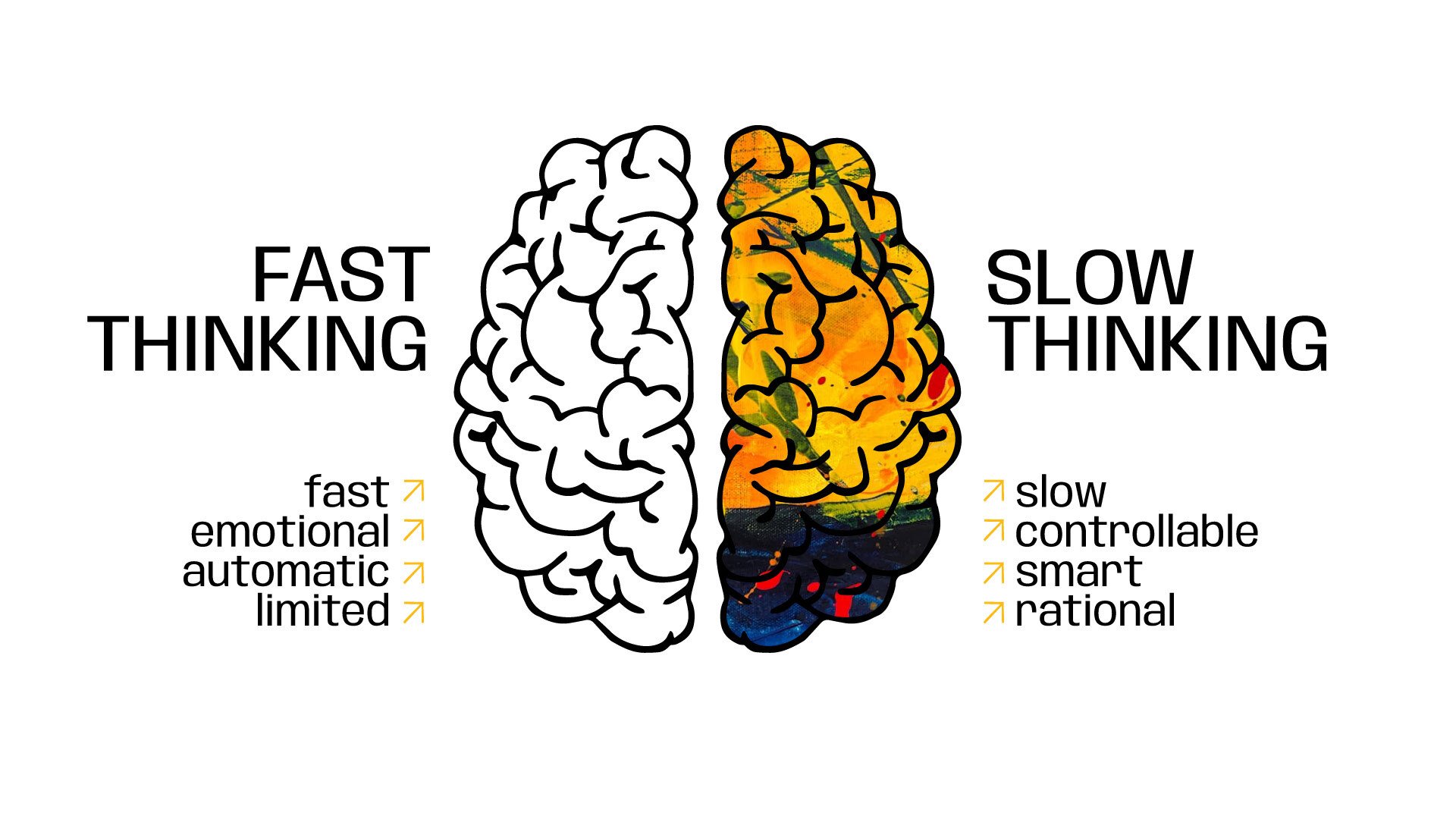

The lazy brain:

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman explains that deep learning requires "System 2"—the slow, effortful part of our brain. But System 2 is lazy. If it isn't "hooked" by a practical problem, it hands control back to System 1, which promptly starts thinking about lunch or checking LinkedIn.

The Internal Trigger:

Nir Eyal, author of Indistractable, points out that distraction is often an escape from discomfort. Boring theory is uncomfortable. Your brain seeks "traction" elsewhere to escape the "distraction" of a dry lecture. As Gabor Maté describes in Scattered Minds, our modern environment creates a sense of "fidgetiness." We cannot expect people to sit still and absorb abstract concepts when their minds are conditioned for constant movement.

Moving from Theory to Experience

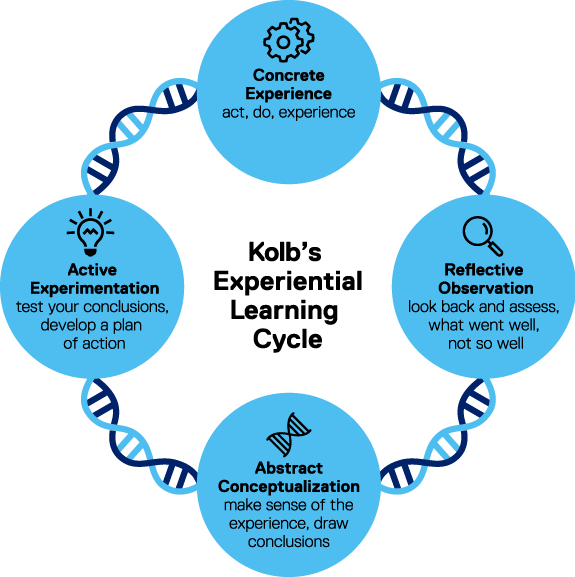

If we want to actually learn, we have to stop reading and start doing. This is where David Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle becomes the ultimate framework for a training revolution.

To explain it like you’re ten: Learning is a circle, not a one-way street.

Kolb’s learning cycle

Do (Concrete Experience): You jump in and try. No instructions. You fail, you succeed, but you feel it.

Think (Reflective Observation): You stop and ask, "What just happened? Why did that fail?"

Learn (Abstract Conceptualization): Now I give you the theory. Now the slide on "Scrum Values" isn't a definition; it's the answer to the problem you just had.

Test (Active Experimentation): You go back in and try again using the new "answer" to see if it works better.

To put it in simpler terms that can be applied to how to teach courses or trainings, you can look at it this way:

Connection - Link the information you’re about to give to the past. Hook the brain and activate the System 2 (Kahneman). Start with a question: “Have you ever been on a team where x happened?” - or do a 5 minutes challenge

Concepts - The “need to know”. Give them just enough theory to solve the problem. 10-15 minutes of slides maximum. Use visuals and stories. No Bullet points. Research shows that the adult attention spans drop-off after 10 minutes without a Step 1 or Step 3 activity.

Concrete practice - The “DO”. Apply the concept immediately. Do a simulation. A role-play or “find the red-flag” exercise in a sample backlog, for example.

Conclusion - The “Commit”. Summarize and plan for real-life use. Ask: “How will you use this on Monday?” Or a quick 1-minute “teach-back” to a partner of their choice. As per Kahneman, the system 2 is lazy. Try not to give your students the answer to the question. Challenge them to give it to you, to retrieve the answer from their own experiences. Make them use THEIR thinking system 2. This is called active retrieval technique that you can use also on yourself when you’re learning something (by the way, this is why googling stuff is not the best for your brain; try remembering it instead before giving up to the search bar).

Conclusion

The era of "Death by PowerPoint" must end. We cannot expect to transform a corporate culture by feeding people’s System 1 with dry slides while their System 2 is screaming for a way out.

If we want to change how people work, we have to change how they learn. We must move from Information Obesity—where we consume endlessly but digest nothing—to Experiential Mastery.